You’re invited but your friend can’t come: Iran and Geneva II

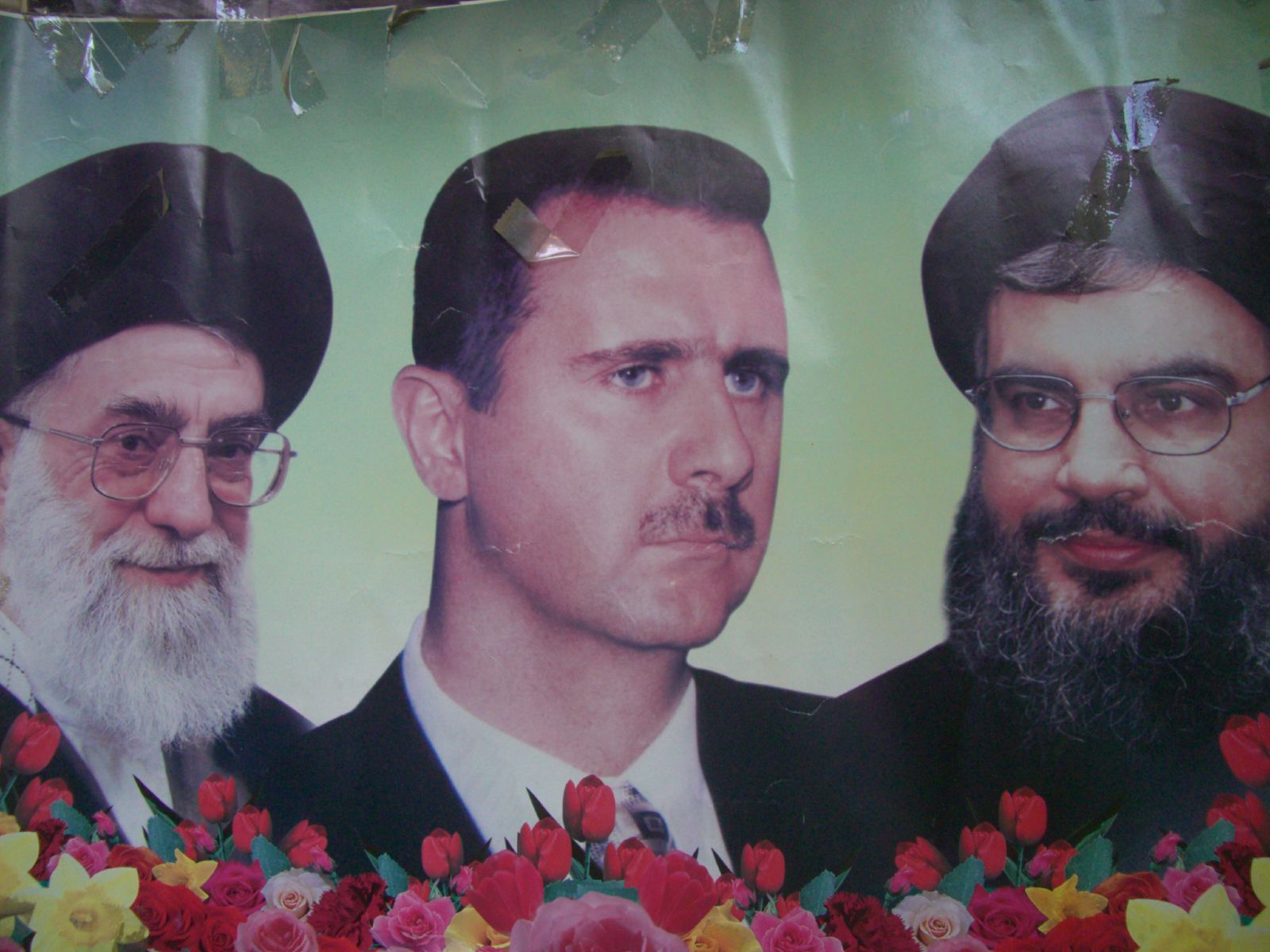

/Left to Right: Iran's Ayatollah Khamenei, Syria's President Bashar al Assad, and Hezbollah's Hassan Nasrallah

(Photo: Christopher Wilken | Flickr)

By Eric Bodenkircher

The successful American attempt to prohibit Iranian participation at the Geneva II peace talks on the Syrian crisis is a mistake. By excluding Iran, the United States action ignores the traditional political behavior of the ethnic and religious communities in the Levant and thus significantly decreases the chances of achieving tangible results in Geneva.

Today Syria is a failed state. The absence of governance has created a society riddled with ethnic and religious conflict and has exposed it to considerable external interference by state and non-state actors. As a failed state, the religious and ethnic communities of Syria have sought external assistance to ensure their existence and political survival. One of those religious communities, the Alawites, has been largely represented by the Asad regime. In their fight for survival, the Asad regime has and will continue to rely on Iran for support and assistance. The patronage provided by Iran to the Asad regime has little to do with the similar religious beliefs of the regimes and more to do with strategic depth and political assurances.

The strategy of looking to outside powers to protect one’s regime/community is not unique to Syria. One needs to look no further than Syria’s neighbor, Lebanon to find another example. For the past two centuries, the ethnic and religious communities of Lebanon have engaged outside entities for assistance and to strengthen their hand vis-à-vis their opponents. In 1839 the Druze minority approached the British for support to counter the growing relationship between the Maronite Catholics and the French. The Lebanese President Charles Helou explicitly told the US Ambassador in 1969 that he could take a harder line against the PLO and leftists if he were confident of US support. Elements of Lebanon’s Shia community sought Iranian support as it fought the Israeli presence in South Lebanon. And after distancing himself from the United States and France, the acting Lebanese Prime Minister, General Michel Aoun resorted to Saddam Hussein’s Iraq for assistance from 1988-90.

Lebanon also provides a vivid example of a failed peace agreement attributable to the absence of relevant political actors in negotiations. In May 1983, the United States brokered a peace agreement between Israel and Lebanon. Although Syria maintained significant military forces in Lebanon and had an extensive array of Lebanese allies, they were excluded from the negotiations. The US only sought Syrian acquiescence to the agreement after negotiations concluded. Without Syrian support, the May 1983 agreement was stillborn. Syria’s Lebanese allies successfully worked to prevent the implementation of agreement and worsened an already devastating Lebanese conflict.

As long as Iran remains a political player in the Levant, a region that is becoming increasingly polarized as a Sunni/Shia conflict, it must have a presence in the Syrian crisis negotiations. Without its presence, communities (i.e. the Alawites and the Twelver Shia) that look to Iran for support and protection will inevitably feel threatened and perceive that their backs are against a wall during negotiations. As a result, they will be intransigent in negotiations or unwilling to adequately implement their results.

Suffice it to say that without Iranian participation at Geneva II any agreement will not be worth the paper it is written on. And if Iran continues to be marginalized, expect instability and violence in Syria and throughout the Levant to be the norm for years to come.

Eric Bordenkircher is a Doctoral Candidate in Islamic Studies at UCLA.